Sydney at the end of the world

Visions of a dead Australia

I’m taking a lockdown brain-inspired detour into pop culture this week.

Decades of encroaching cultural imperialism mean that few things ignite the passions of Australians more than seeing our culture refracted in the Hollywood kaleidoscope. A minor reference to Australia in a popular movie or TV show is likely to ignite discourse. Even those who consider themselves above the cultural cringe inevitably dine at the same trough. Notice me, senpai!

One trend that has gone largely unremarked upon is Sydney’s increasingly entrenched place in the cinematic language of apocalypse. There are numerous examples in recent years of the harbour city skyline appearing in Hollywood visions of catastrophe in smoking ruin; easy shorthand for the fact that whatever doom has been visited upon Earth is in fact global in reach.

Some examples:

The reason for Sydney’s increasingly prominent place in doomsday montages is pretty obvious. There really aren’t that many cities in the world which can be identified within seconds by a primarily Western audience, and it gets a bit dry only showing obliterated versions of New York, London and Paris. Between the arches of the Harbour Bridge and the sails of the Opera House, there’s very easy iconography to include as an instant reference point.

But there’s also a surprisingly rich vein of history there. Sydney, with its history as a far-flung port city on a mysterious continent, has been the focus of apocalyptic visions long before the marketing team for The Day After Tomorrow put a submerged Opera House on its posters. And Australia itself has also played that role in the global imagination.

Sydney features prominently in H.P. Lovecraft’s influential 1928 short story “The Call of Cthulhu”, which concerns a global cult trying to awaken a sleeping alien god who is entombed in a drowned city at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. Lovecraft, who was as provincial and paranoid as they come, never travelled too far beyond New England, and it’s obvious most of his knowledge of Sydney was gleaned from an atlas or encyclopaedia:

After that I went to Sydney and talked profitlessly with seamen and members of the vice-admiralty court. I saw the Alert, now sold and in commercial use, at Circular Quay in Sydney Cove, but gained nothing from its non-committal bulk. The crouching image with its cuttlefish head, dragon body, scaly wings, and hieroglyphed pedestal, was preserved in the Museum at Hyde Park; and I studied it long and well…

Circular Quay… so exotic…

Lovecraft later returned to Australia in 1935’s “The Shadow Out of Time”, which describes a race of cone-shaped aliens named the Yith who built a “library city” millions of years ago in Western Australia, now buried under the Great Sandy Desert. A racist even by the expansive standards of his day, Lovecraft was strongly influenced by literary antecedents of the ‘savage continent’, which so amply (but narrowly) explored Africa and Australia’s Pacific neighbours.

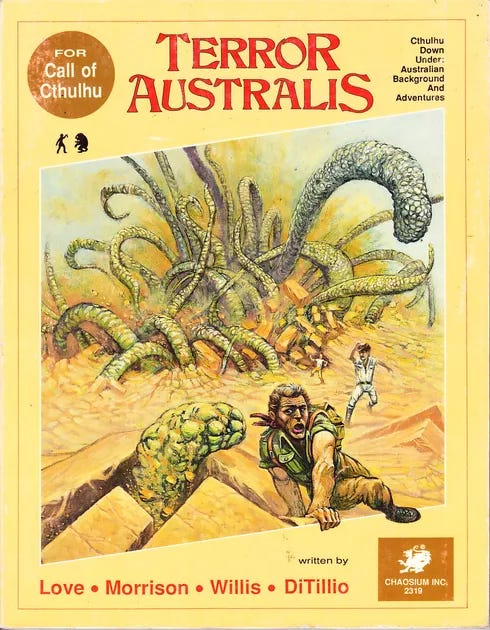

A supplement to the popular Call of Cthulhu tabletop roleplaying game (think horror Dungeons & Dragons) named “Terror Australis” was published in 1981, outlining a number of playable scenarios which synthesise cosmic horror with Aboriginal mythology1.

Similar themes emerge in Peter Weir’s under-appreciated 1976 classic “The Last Wave”, where Richard Chamberlain plays a Legal Aid lawyer tasked with defending four Aboriginal men who have been accused of murder. All the while, he shares with them mystic visions of the end of the world as freak rainstorms batter Sydney. The film culminates with an enormous tsunami approaching the coast.

(There’s also corpus of contemporary fiction, like Claire G. Coleman’s “Terra Nullius”, the TV show “Cleverman” or the audiovisual art collage “Terror Nullius” which treats European colonisation as its own kind of apocalyptic or dystopian event.)

British novelist Nevil Shute’s 1963 novel “On The Beach”, written after he had migrated to Australia, inverts the tradition by depicting Australia as the final redoubt of humanity after a nuclear exchange2, with Melbourne largely going on as normal, awaiting the tides of nuclear fallout to eventually travel south and kill everyone. Australian cities slowly wink out of existence as the southernmost port awaits its doom. You probably don’t have to strain very hard to find some synchronicities with the pandemic.

Of course, there’s “Mad Max”, which has forever merged Australia and civilisational collapse in the broader cultural imagination. The now virtually universal understanding of what a post-apocalyptic society might look like cinematically (parched desert, ruined urban landscapes, marauding gangs of raiders) was more or less set in stone by George Miller and company, pulled together from a series of sci-fi influences and given an Australian flavour — which has now been almost entirely universalised.

It’s telling then that Australia’s cinematic value as a staging ground for the end times also makes its way into the broader discourse. As a country reliant on a relatively thin strip of coastal arable land, it is particularly vulnerable to climate change, and the consequences of a hotter climate are experienced like a disaster movie: raging bushfires, desertification, oceans of dead white coral.

But anyway. No matter what happens, I am excited to see further examples of the Opera House and Harbour Bridge destroyed by various means on screens large and small.

If you can get your hands on a PDF of the original sourcebook — now preserved by the National Library — it is a pretty interesting time capsule of an early ‘80s view of Australian and Aboriginal history.

A nuclear exchange which begins when Albania lobs a nuke at Italy (?)

The Wandering Earth II (2023) had a scene in which the Sydney Opera House was destroyed by a meteor, which by the way is completely submerged form reasons I don't want to share here because spoilers

Also The Matrix, filmed in Australia, used the same imagery.