Campfire tales

This week: Digital peasants, the creator economy and "the first cryptid of the latent space"

Welcome to this week’s free edition of The Terminal. If you’d like to become a paying subscriber and get more content, hit the button below.

Toiling in the fields

Rest of World has a feature on Critterz, a play-to-earn NFT game built on top of Minecraft that (like Axie Infinity before it) turned into a kind of digital sharecropping operation where wealthy players would lease their assets to low-income earners in the Philippines and take a cut of the tokens they earned. As I mentioned in a newsletter a couple of months ago, Minecraft developer Mojang unilaterally banned NFT and blockchain products in their game, which threw nascent gaming economies like Critterz into a tailspin.

The feature interrogates the social and economic structures that have formed around play-to-earn games, and it’s a great read. But one standout for me is this little tidbit, quoting a NFT gaming consultant:

But he also envisions NFT games that could exploit the wealth gap between players to deliver a different experience. “With the cheap labor of a developing country, you could use people in the Philippines as NPCs (“non-playable characters”), real-life NPCs in your game,” said Kossar. They could “just populate the world, maybe do a random job or just walk back and forth, fishing, telling stories, a shopkeeper, anything is really possible.”

Putting aside the fact that there’s nothing about this concept that really demands the use of the blockchain or NFTs, it’s nice to see someone reconstructing the more dystopian promises of the metaverse as an intentional part of the sales pitch. Rather than having the various basic functions of a digital world performed by programmed characters performing a simulacra of personhood, you can be thrilled in the knowledge it’s a real guy who lives in Cebu City, and he’s doing it to feed his family.

In a prescient 2017 article for WIRED titled “Face It, Meatsack: Pro Gamer Will Be the Only Job Left”, writer Clive Thompson sketches out a future where displaced workers from industries experiencing pressures from automation and other shifts in the global order will serve to populate online communities experienced by a superstrate of wealthy gamers who crave “vibrant communities” to spend their money in. “Rich players don’t want to play with bots,” he writes. “They crave the social fellowship of real humans. And they also enjoy the thrill of lording their socioeconomic status over others.”

Despite the consultant in the Rest of World article pitching it as a bold new future for NFT gaming, this sort of perverse class system has already existed for a very long time in online games. Less affluent players from the developing world already form a functional underclass in MMOs like World of Warcraft, where they perform services for wealthier players that are compensated either with in-game rewards or real currency. Wherever a virtual world exists, it will inevitably replicate many of the incentive structures of the real world, including one of its most enduring dynamics: those with a lot of money and no time doing business with those with no money and a lot of time.

Generally speaking, those games are not explicitly built to sustain that sort of social order, and in many cases try to actively discourage it through either technology or policy. What is interesting is a new generation of metaverse developers making a class system part of the living texture of their worlds, making it more believable and enjoyable for the section of the playerbase who reliably spend money.

$XXX

A chastening reminder of where the real energy in the creator economy lies, despite the millions of words expended on arguing about free speech and influence on Substack. More from Variety:

The U.K.-based company on Thursday announced financial results for the year ended Nov. 30, 2021. OnlyFans’ net revenue grew 160%, to $932 million, and the company had pre-tax profits of $433 million (up from $61 million in 2020), its biggest yearly growth in profits.

OnlyFans creators earned $3.86 billion in 2021, an increase of 115% from the year prior, bringing the company’s payments to creators to more than $8 billion since its 2016 founding. Gross revenue (i.e., fan payments net of taxes) also more than doubled, to $4.8 billion, for the year ended November 2021.

It’s often said that porn is the dark matter of the internet, and this has led to slightly defective analysis — like the widely held, but not entirely accurate, belief that the porn industry ultimately picks the winner of competing media standards and formats. (No, porn isn’t actually the reason VHS beat Betamax.)

But those OnlyFans numbers are crazy, especially given it runs a much leaner operation than most other creator economy platforms. This is no doubt why, as Casey Newton reported at The Verge, Twitter was strongly considering building its own competing adult content platform, as opposed to just being a marketing channel for others:

In the spring of 2022, Twitter considered making a radical change to the platform. After years of quietly allowing adult content on the service, the company would monetize it. The proposal: give adult content creators the ability to begin selling OnlyFans-style paid subscriptions, with Twitter keeping a share of the revenue.

Had the project been approved, Twitter would have risked a massive backlash from advertisers, who generate the vast majority of the company’s revenues. But the service could have generated more than enough to compensate for losses. OnlyFans, the most popular by far of the adult creator sites, is projecting $2.5 billion in revenue this year — about half of Twitter’s 2021 revenue — and is already a profitable company.

Violent delights

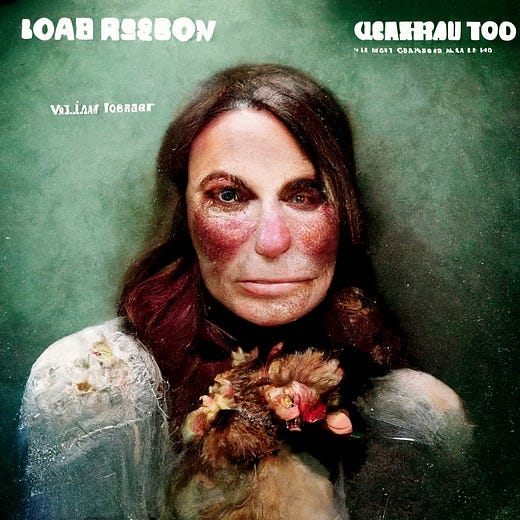

The emergent AI art space has its first widespread bit of horror creepypasta. Or, as one replier put it, the “first cryptid of the latent space”.

Twitter user Supercomposite was playing around with an unnamed AI image generation model and experimenting with a technique called negative prompt weighting. Usually with these systems you’ll feed it a prompt and the neural net will draw upon its vast corpus of visual and textual data to generate an image that most closely resembles the content of said prompt. Negative weighting involves the opposite — you’re telling it to generate an image that isn’t like the prompt.

Supercomposite threw the AI the word ‘Brando’, as in Marlon Brando, instructing it to generate something as far from the actor as possible. It spat out what looked like a corporate logo for a non-existent company with the vaguely Pynchonian moniker ‘DIGITA PNTICS’. Wondering whether executing the experiment in the inverse would then produce a picture of Marlon Brando, she dutifully entered DIGITA PNTICS as a negatively weighted prompt. Instead of a picture of Brando, it created what she described as a “devastated-looking older woman with defined triangles of rosacea on her cheeks”. Supercomposite named this woman ‘Loab’.

The creator went on to experiment further with the original Loab image and the model, combining it with other AI-generated images and further prompts. She claims that the imagery became increasingly bizarre, and the face of ‘Loab’ appeared recognisably through multiple generations of images — sometimes disappearing, but inevitably coming back, sometimes in quite abstract ways. What elevates it to the level of horror is the goriness and violence of the images. "Through some kind of emergent statistical accident, something about this woman is adjacent to extremely gory and macabre imagery in the distribution of the AI's world knowledge," she writes.

The thread went viral this week, with a nice mixture of responses ranging from enjoyment of a grisly bit of internet horror to those who seem to genuinely think it is inviting a real-life demonic entity across the threshold. You can, as Max Read writes, imagine that “across a number of offices in Los Angeles people are already pitching Loab movies to bored agents and executives.”

If you want to be a cynic, you can say that Supercomposite’s storytelling is doing a lot of the heavy lifting in that thread, and that the pictures aren’t that similar, beyond what one might expect from feeding similar prompts and images into the AI’s maw. But it’s not hard to see why it has resonated so strongly. This isn’t unexplored thematic terrain, even beyond the realm of internet fiction. The notion of otherworldly sentiences manifesting through technology is a well-worn trope in horror and science fiction, and here we have the added weirdness of a computer spitting out imaginary demons in response to incantations, like a digital ouija board.

The parallel theme of photographs and images being haunted by malevolent entities captures a general unease about the nature of content creation and consumption. In Stephen King’s 1990 novella The Sun Dog, a Polaroid camera purchased in a junk store only produces images of a malevolent black dog which approaches the frame with each successive photograph. In Scott Derrickson’s 2012 film Sinister, a pagan demon manifests in Super 8 footage discovered in the basement of a house where a multiple murder occurred. I could go on with more examples, but I won’t.

This narrative archetype, of which you can find antecedents in various folkloric traditions, also has a habit of breaking out into contemporary urban legend. Students at the Royal Holloway College at the University of London for the better part of a century have traded stories suggesting Edwin Landseer’s macabre painting Man Proposes, God Disposes is haunted, and one of the earliest creepypasta memes of the 21st century generated a similar mythology around artist Bill Stoneham’s unsettling 1972 painting The Hands Resist Him.

So there’s certainly something latent in the terrain of the human creative consciousness that our friend Loab speaks to. But there’s something else interesting going on here too. AI image generation has advanced in leaps and bounds recently, becoming both more impressive and more accessible at incredible pace, but even the most sophisticated of them veer more often than not into the uncanny valley. Among the most active and vibrant communities emerging in AI art are those leaning into that inhuman strangeness to create spooky images.

Indeed, it seems like that particular genre of imagery is what AI is actually best at right now, as a natural consequence of its technological imperfection. We can probably expect more Loabs as artists continue to play around in the unexplored territories of AI art.

I’ll close off this section with a quote given to PC Gamer by David Holz, founder of image generation platform Midjourney, on the place of violent and scary imagery in AI. “Obviously, it doesn't matter if there's a little bit of gore,” he said. “But the problem is that you have 10,000 people who want to do gore all day. Then we produce more gore content in one month than all of human visual history. I don't know if we need that.”

Star power

An important dispatch from the far-flung provinces of an overstretched empire:

It’s been remarked upon before, but one of the least edifying aspects of the internet and streaming-enabled content bubble is how it mainstreams the impulse once exclusive to fan fiction of leaving absolutely no narrative thread unpulled or unexplained. There’s always a new show or movie waiting in the wings to obliterate whatever alluring skerrick of mystery might be left in the spaces between existing properties.

In this case, Disney can’t even let its esoteric cosmology go unexplained. Sad!

Elsewhere

A story here from Katie Notopoulos at BuzzFeed which tickles my enduring interest in the cultural grey economy that has sprung up around music streaming platforms. She makes the case that a bunch of musicians who have recorded scatological ditties with titles like "Poopy Diaper" are profiting (inadvertently or otherwise) from little kids yelling rude phrases at Amazon Alexa.

A good essay at The New Atlantic on on the gamelike nature of online existence, and the various new sensemaking techniques we apply to life and politics. “We build online identities with the same diligence and style with which Dungeons & Dragons players build their characters, checking boxes and filling in attribute fields.”

What comes next for the ‘creator economy’ — a category that has become so broad and overstuffed that it is losing meaning? “At the same time, the shift to individuals versus institutions is, I believe, a real and lasting phenomenon. You can’t see over 10,000 people showing up at the ghastly American Dream mall in New Jersey for a YouTuber’s new burger joint and not recognise there’s a cultural shift at work.”

A fun story about an internet mystery that spread on social media this week. The writer has an old family photo with a TV shown in the background displaying an obscure cartoon he had never been able to identify, and the social media hivemind took a while to figure it out too.

Interesting report on Apple’s quiet efforts to build up an advertising empire now that it kneecapped competitors like Facebook and Google with its app tracking reforms.

A thread describing what happened among eager Wikipedia editors when the Queen died.

A forums thread featuring someone using an AI image generator to turn old Sierra adventure game images into modern high-resolution art.

On the role of advanced chips in the Russia-Ukraine War, and the effect of Russia’s ongoing failure to obtain them.

Blackbird Spyplane interrogates a new trend in car paintjobs, which resemble featureless wet putty — “almost as though a computer-rendered object has somehow infiltrated the real world, beholden to a slightly different set of physics.” Can’t say I’ve seen too many of these in Australia, but now I’m impossibly attuned to their arrival…

“El Salvador Had a Bitcoin Revolution. Hardly Anybody Showed Up.”