Casinos, computers and cities

Welcome to this week's free newsletter

Welcome to this week’s free edition of The Terminal. If you’d like to become a paying subscriber and get access to more posts, hit the button below.

Red letters

The above is a troubling thread of letters to the judge in the bankruptcy case of cryptocurrency lender Celsius, which underwent a spectacular collapse over the past couple of months

Here’s the shortened version of the Celsius story, for those unaware. Founded in the crypto surge of 2017 and pitched with the radical language of ‘debanking’ and ‘replacing Wall Street with the blockchain’, the company facilitated lending and borrowing for its users, who could deposit a range of tokens and digital assets to lend and borrow against. It promised mind-bogglingly high yields for doing so, which made it attractive for a wide range of investors, who entrusted the company with over $12 billion in funds under management at peak.

Despite its claims to be sticking it to the Wall Street elite, it turned out Celsius was supporting its high yields in part by pumping customer money into risky DeFi protocols, which you might fairly describe as equivalent to putting it in a big sack and taking it down the greyhound racetrack. It was not, as founder and CEO Alex Mashinsky repeatedly asserted, safely collateralised lending. There’s a good Twitter thread here from last month which goes into some detail about what some of these odd plays were.

This made it increasingly challenging to manage risk, and when the crypto market plunged, all those bets unwound at pace. In June, Celsius posted a blog titled — hilariously, in retrospect — “Damn The Torpedoes, Full Speed Ahead”, which denied persistent rumours the company had dumped customer funds into bad investments and was facing a serious liquidity crisis. These claims were dismissed as “misinformation”, in line with the general crypto mandate to decry any legitimate criticism whatsoever as FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt).

Quite literally seven days later, on the same blog, Celsius announced it would pause all customer withdrawals, swaps and transfers, citing “extreme market conditions” as depositors made a run on their assets amid the crypto crash. That pause ended up being permanent. It tried to recover its position before declaring bankruptcy this month. Vale.

Anyway: the letters. The collapse of Celsius has left a lot of people, many of whom are average, unsophisticated investors lured by the phenomeal promised rates of return, out in the cold. The thread above documents many people who say they have lost their life savings, and it makes for very grim reading.

I don’t really need to add to the scads of comparisons made online between the dynamics of crypto and multi-level marketing schemes, but it’s not hard to observe that specific topology of despair in these letters to the judge. You see a common thread in many of them: these people were drawn to both the promise of easy riches as well as Mashinsky’s messianic promises of liberation from the old system. One representative example:

Much of my life’s savings are currently held hostage on the Celsius platform. Alex Mashinsky week after week promised the community that our funds were safe and not being used in any risky lending. Every week during his AMA’s he promised that Celsius had the funds to cover all user assets and that under no circumstances were our funds at risk.

Or:

My life savings were in Celsius. I trusted Alex. I pray and hope everyday you are doing everything in your power to rightfully return deposits back to customers. I can’t tell my wife and kids our retirement and dreams have been stolen from us. Life is stale, we need updates and silence is not the answer. Please I request you to help put the interest of unsecured creditors, or as Alex famously called his “community” first.

There’s a lot in here which speaks to a yawning gap between the promise of crypto and Web3 as some long-promised return of power and capital to ‘the people’ and the common reality: some combination of over-leveraged hedge fund, unregulated casino and Discord tent revival.

I wonder whether that sort of messaging is going to see a shift next time around the sun. Probably not.

Blocked!

While we’re on Web3-ish subjects, there was an interesting development from the sick, sad world of NFTs this week. Minecraft developer Mohjang, which is owned by Microsoft, issued a unilateral ban on users and developers integrating the blockchain and NFTs into the game. This instantly obliterates projects like NFT Worlds, which have built bespoke NFT economies on top of Minecraft in order to benefit from its existing developer ecosystem and absolutely massive player base.

I was particularly taken by the reasoning offered (my bold):

Each of these uses of NFTs and other blockchain technologies creates digital ownership based on scarcity and exclusion, which does not align with Minecraft values of creative inclusion and playing together. NFTs are not inclusive of all our community and create a scenario of the haves and the have-nots. The speculative pricing and investment mentality around NFTs takes the focus away from playing the game and encourages profiteering, which we think is inconsistent with the long-term joy and success of our players.

This is not a particularly radical opposition to NFTs and other blockchain applications (in fact, it’s basically objection number one) but it’s interesting to hear from a major game developer, many of whom have been delicately managing the politics of placating their customers while leaving open the door to profiting from the pre-crash NFT craze.

The current debate within the broader gaming community about NFTs is a really interesting digital culture in miniature. For some time, Web3 boosters have insisted that gaming will be the crucible for broader blockchain adoption, and that gamers will be at the centre of a coming cultural revolution around digital ownership. In practice, the vast majority of gamers and individual developers (in the West, at least) are violently opposed to it, to the point that working for a blockchain company has basically become a black mark within significant parts of the industry. Despite the best efforts by evangelists, that situation isn’t changing fast.

There are plenty of reasons for this. Firstly, most gamers consider NFTs to be little more than a new vector of profiteering and rentseeking, aided by the fact that some of the most mercenary publishers have expressed an interest in exploring them. Secondly, most NFT and crypto games right now are terrible garbage. You can put that down to the fact that it’s still early days, but there’s also a defective mentality behind most of these projects. They’re built as speculative economies first, with the actual gameplay — crucial to gaming, some might argue! — becoming secondary to the casino.

There’s no better example of this than Axie Infinity, the vaguely Pokémon-esque NFT game which evolved into a digital sharecropping scheme for poor workers in the Philippines. The core gameplay wasn’t very good, and it was abundantly clear no one would be playing it without the speculative earning aspect. Once the air went out of the Ponzi and it was no longer feasible to earn an extremely minimal living playing it, it went to shit. Turns out no one was battling these awful little beasts for fun.

So it was interesting to see Mohjang — and, by extension, Microsoft — betting against NFTs and their role in gaming in very explicit and critical terms.

In the NFT Worlds Discord, where there was once a widespread (and unfounded) belief that Microsoft might actually acquire their project, theories abound that this is a conspiracy to eliminate competition before Mohjang unveils its own system of digital ownership. Maybe, but it’s an interesting signal of the sentiment out there regardless.

Art heist

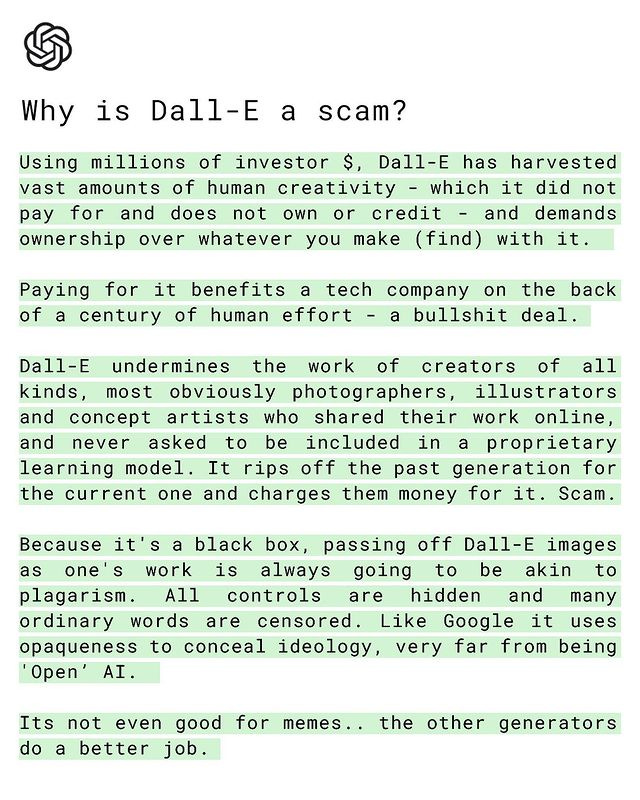

A take here from artist David O’Reilly, of a genre I think will gain plenty of traction as various kinds of generative AIs like DALL·E become more widespread.

The argument is basically this: these models are trained on millions and millions of images indiscriminately sucked up from the internet. Very few (if any) of the creators of those images consented to their work being used to train a robot, and the opaque nature of the system means it will never be clear exactly what ‘influences’ might have gone into creating any given image. By commercialising its product, OpenAI is profiting from the labour of millions of artists and creators, living and dead, in a vast, borderless act of plagiarism.

The counter-argument to this, which I’m also seeing spring up, is that these image models represent a rough simulacra of creativity itself. Everything is a remix, and everything you create is necessarily guided by the accumulation of your influences in some undefinable concoction. To think of your creativity as purely emergent versus whatever DALL·E is doing is simply giving yourself too much credit. You’re plagiarising all the time too, you dog!

I’m personally not entirely sure where the chips fall here. I’m hugely unconvinced by any counterargument which assumes the human mind works in roughly the same way as a computer. But at the same time I find it hard to discern an obvious harm on behalf of literally every artist in human history who has had their work digitised. Either way, I expect it to pop up a lot in the coming years, and I assume there will be some curly questions about copyright which might one day be tested in court somewhere.

High fidelity

I fell down an internet wormhole this week watching videos like the above, which show earlier high definition video experiments before the format became standardised and widespread in the 21st century (mostly thanks to Hollywood).

Attempts to create a HD standard for television and broadcast are much older than you’d think. The Soviets even gave it a crack in the 1950s with the somewhat imposing name Transformator, which had the extremely non-commercial goal of producing ultra-crisp teleconferencing for the military high command. The above clip, which the uploader assumes is likely shot in 1993 on a Sony HDVS camera like the HDC-500, was part of a marketing effort for the relatively small high-def VHS market, which never took off. For a variety of reasons, including cost, it wasn’t practical.

Anyway. There’s a weirdly fantastical element to watching clips like this. Our cultural memories of certain eras are inevitably guided by the media and video formats of the age. As a result, your memories of the nineties are probably heavily connected to not only the movies and television shows of the era, but also news broadcasts and home videos. When you picture ‘the nineties’, you’re probably naturally picturing it with the washed out sheen of a VHS tape, or the fuzz of a CRT television. It helps that so much cultural and visual history of the era is now uploaded to YouTube and Facebook replete with those visual artefacts, plus the fact those aesthetics have a nostalgic and aspirational cool to them now.

So it feels somehow wrong and inauthentic to see a New York City streetscape in 1993, full of obvious visual markers of the era, in widescreen and high definition. It doesn’t cohere. There’s a good playlist of similar videos here if you’re interested.

Elsewhere

Readers of this newsletter will know one of my pet fixations is Wikipedia and how people use it for all sorts of creative purposes beyond its intended purposes. I’d never seen this wiki page, which is like an FBI Most Wanted list of the site’s most pathologically obsessed vandals. Some truly interesting characters detailed within, including someone who “frequently inserts unsourced and untrue information about cast changes for Broadway shows, casts for upcoming tours, or cast for upcoming shows”.

Excellent and very long piece on the luxury yacht industry. As depraved as you might imagine, and more!

On the odd online culture of ‘transvestigators’: a highly weird anti-trans community who sit online all day analysing photos of Henry Cavill and Elon Musk to figure out if they were assigned female at birth.

This 2020 interview with director Brian De Palma. Adjacent to what I wrote about streamcore last month.

The things that they’re doing now have nothing to do with what we were doing making movies in the ’70s, ‘80s and ’90s. The first thing that drives me crazy is the way they look. Because they’re shooting digitally they’re just lit terribly. I can’t stand the darkness, the bounced light. They all look the same. I believe in beauty in cinema. Susan and I were looking at “Gone With the Wind” the other day and you’re just struck at how beautiful the whole movie is. The sets, how Vivien Leigh is lit, it’s just extraordinary. If you look at the stuff that’s streaming all the time, it’s all muck. Visual storytelling has gone out the window.

Enjoyed this on the hard seltzer craze, and how everyone is waking to the realisation that — buzzy branding aside — White Claw and its legion of copycat pretenders basically just aren’t very good. Strange moment in the culture.

On the timeless fear of parents and new technology, and “watching kids go where adults can’t follow”.

A feature in Bloomberg on how crypto hedge fund Three Arrows Capital imploded.

“How a small airport in central Kenya became a hub for high-end electronics imports.”