Secret whispers and art history

Tip: read this newsletter in the Uber on the way to the pub

Welcome to this week’s free edition of The Terminal. If you’d like to become a paying subscriber and get access to more posts, hit the button below.

Art attack

While scrolling my Twitter feed I came across a link to a e-book named The DALL·E 2 Prompt Book, which is pitched as “a free visual resource to inspire your own creative DALL·E projects”. Practically, it’s an instructional text for how to start making your own AI art with the DALL·E 2 beta, laying out for a novice how to best structure and write prompts for visually interesting results.

It’s certainly useful as far as that goes. But this innocuous PDF, as an artefact, actually got me thinking about the broader social and cultural implications of this tech in ways the application itself didn’t.

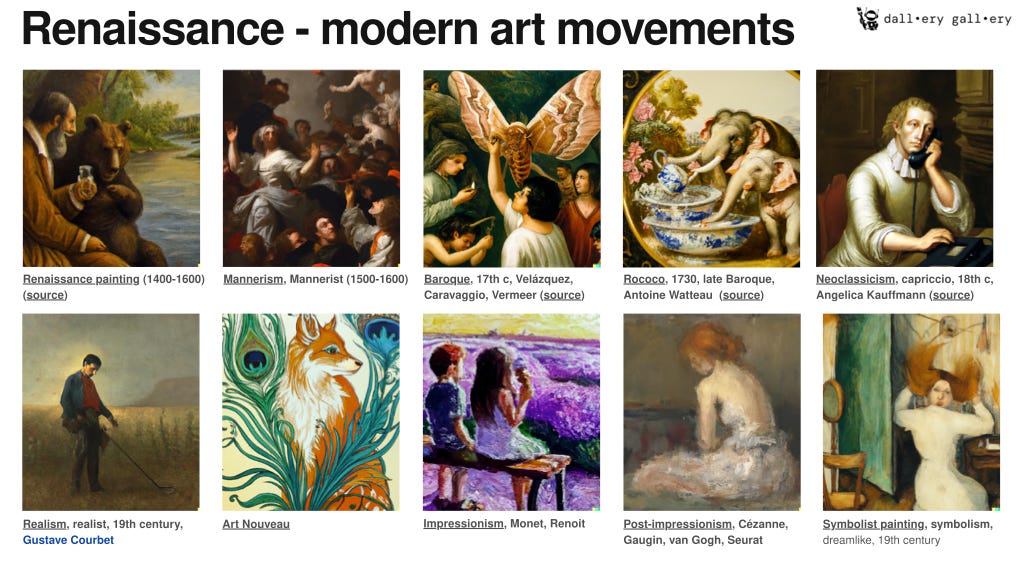

As you can see in the screenshot above, there’s a lengthy section of the ebook which is dedicated to various art movements and artists throughout history, the names of which can be plugged into DALL·E to entice the neural network to produce images that imitate their various aesthetic characteristics. In my own experiments, I’ve found it can be startling adept at reproducing the style and vibe of broad artistic movements, and somewhat good at imitating individual artists. (For some heavy hitters with a huge corpus of images and mimetic impersonators, like Van Gogh, it tends to perform a lot better.) You can safely assume the deficiencies will be ironed out in future models.

There’s something profoundly dislocating about seeing sweeping artistic movements and milieus reduced to floating signifiers and cheat codes to be plugged into an input box. Movements that were inextricably tied up with their historical and political contexts, many of them quite radical, become a set of discrete, bloodless patterns for an algorithm to reproduce through a complex process of pixel diffusion. Divorced of context, they become like entries in a fabric sample book to be selected and applied at will.

It raises questions, then, about the future of creative production. I’ve said a few times in the august pages of The Terminal that I think neural networks and language models are going to have a profound impact on society and culture now that the genie is out of the bottle, in a way that might be subtler and less overt than your usual sci-fi AI apocalypse narratives. (The Economist published a feature on this recently, too.) I think this instruction manual, which essentially recasts thousands of years of art history as a purely functionalist project is one expression of that weird shift. Apologies to everyone from early human cave painters to Bruegel the Elder and Cy Twombly — you are now mere entries in the artworld equivalent of one of those chunky Prima strategy guides for Diablo II.

It’s not entirely clear yet what the near future of creativity looks like subject to pressures like this — it seems these tools right now are mostly being used professionally to assist with early iteration and brainstorming — but there are some obvious implications. How do new artistic movements and design modes emerge in a very plausible world where a computer can instantly and convincingly imitate them? The consumption habits created by the internet have already gone some way to flattening and decontextualising visual culture, but this seems to be another level entirely.

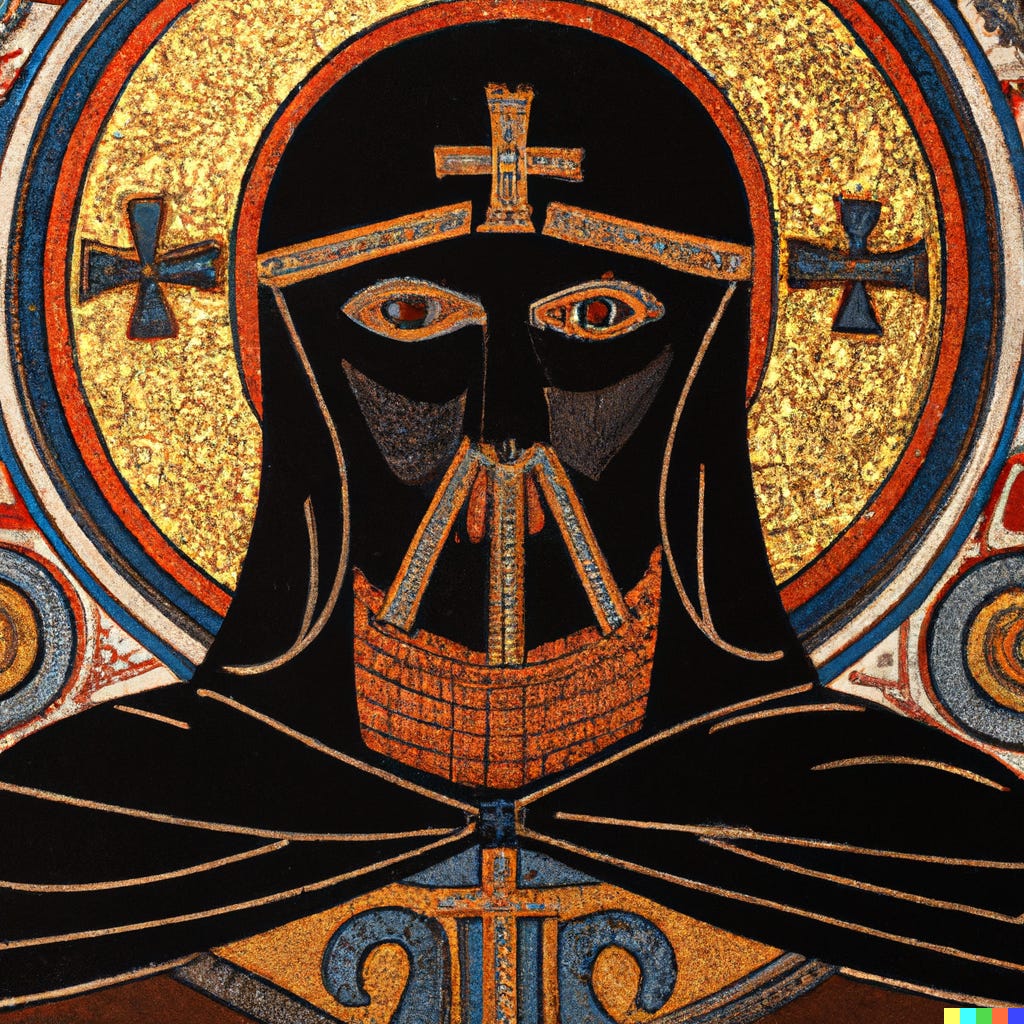

This is ‘Darth Vader as a Byzantine icon’, by the way. Thought you should see it.

Glory, glory, glory

This feels related to the above section somehow:

Shouts and whispers

One extremely minor sector of the tech economy I’m endlessly fascinated by are anonymous messaging and ‘secrets’ applications. At any given moment, there appears to be at least one viral web app spreading through Twitter or Instagram Stories, promising an anonymised question service which will help you ascertain what your friends and acquaintances really think of you. There’s something about the code switching possibilities inherent to anonymous spaces in the largely deanonymised zone of the social web that is obviously very compelling to people.

Curiouscat, Ask.fm, Formspring, Whisper — recent history is littered with dozens of examples, all of which accumulated millions of users rapidly before crashing and burning in the absence of an actual business model. (Last year I wrote for subscribers about the very strange odyssey Whisper went on after its original model failed.)

The latest tranche, including examples like Sendit, Yolo and NGL, are obviously of the view that enough time has passed since the last generation that we can all give it a crack again. They’re much more social-native this time — largely on Instagram, as Snapchat banned the whole field from accessing its API earlier in the year — and, it turns out, mostly illusory. The monetisation hook for NGL is that you can pay for ‘hints’ (i.e. extremely vague location and device data) as to who left the questions.

But much of it doesn’t even appear to be real. From TechCrunch:

When TechCrunch recently tested NGL and its rival Sendit, we copied the provided short links into an Instagram Story that was only live for a mere moment before we took it down. This tricked the apps into thinking we were now awaiting anonymous questions from our friends. A few hours later, questions — supposedly from our friends who saw our link — appeared in the apps’ respective inboxes. But in reality, no one had seen our link, as it was never live long enough to be clicked by anyone, much less by the half-dozen people who supposedly sent us messages, according to NGL.

VICE tried the same experiment with similar results. Is nothing sacred? Can’t we have a genre of app seemingly used mostly for anonymous driveby sexual harassment of women without bots ruining it? Sad times.

Dispatches from the mailbag

In this newsletter I often like making the sweeping statement that the internet has obliterated the monoculture and therefore it will become increasingly challenging to our cultural memory. Basically this tweet:

I wrote a bit more about this in a subscriber post last weekend about why the multiverse and time loops have become so weirdly dominant in mass pop culture. But, for a counterpoint, I asked some readers in an open thread: how will the 2010s be remembered? A couple of highlights…

From reader Ryan:

…I think the mania over these things - including the paranoia over spoilers, the outsized influence they’ve had on other corporations trying to produce coherent interconnected “universes” of IP, the cultural frenzy of people genuinely being excited to go to the theatre to essentially watch an episode of television with no narrative closure - will be remembered as a peak 2010s thing. It’s only been 3 years and I’m already nostalgic for the psychotic frenzy of people gasping and clapping during an opening-weekend Endgame screening.

From Joshua:

I agree that it feels like the monoculture has gone away, and I agree with the thesis in the short term that we are all building a different recent history in our heads. However, I am nearly fifty, and the further I get from the 1980s, there are fewer things that I think everyone would agree was historically significant. In fact, as I think about it, culturally significant and historically significant are drastically intertwined yet completely different. Stranger Things and the MCU are going to be repackaged and sold again and again in the same way that Star Wars and Prince have been. The previous American president or Princess Diana will continue to take different shapes in the telling of their stories. That’s a cultural prerogative; to retell the stories in context of the culture telling the story.

Both of those naturally followed from the conversation about the recent obsession with the multiverse, but feel free to throw in your entries below.

Elsewhere

A remarkably candid interview here with the two founders of MetaMask, which is one of the central engines of the crypto and web3 economy thanks to the fact so many people use it as their wallet for Ethereum-based tokens. In it, they readily admit that the crypto ecosystem they’ve helped power is, as of this moment, largely a nihilistic casino riddled with Ponzi economics and scams. But they hold out hope the next round of experimentation will be better. One point they raise is that the widely publicised phishing scams targeting MetaMask users are really proof that the internet’s security stack in general is defective and vulnerable. That’s definitely passing the buck, but I don’t think it’s entirely wrong either.

The New York Times has a story on the rise and fall of online dollar store Wish, which you no doubt know for advertising incredibly weird deals on social media. In short, increasingly deceptive ads and the global shipping crisis made the Wish model less and less compelling and profitable. But there’s still no better place to go for three-dollar leather jockstraps and assorted plastic teeth.

After the ‘pregnant man’ discourse event that came with the new emojis in Unicode 14.0 last year, the new lineup in the 15.0 update seem positively pedestrian by comparison. I always find it interesting that a consortium of tech giants, typesetting firms and cultural bodies gets together each year and votes on the new frontier of online human expression. People periodically get fired up about whatever new emoji get added in a given year, but rarely is that unusual arrangement remarked on.

From earlier in the year, but I missed it: a story in VICE about an occult author using AI language models to co-write a mystical text — a method they argue taps into the “subconscious mind of the internet”. “Text completion engines like GPT-3 often create these uncanny and unsettling responses. But according to Wurds, the aim of their trilogy of books isn’t to unnerve. Rather, it’s to explore the spiritual potential of a Japanese avant-garde tradition called Butoh, an improvisational dance where the practitioner often ends up in strange, spontaneous contortions.”

Not sure if I agree with the prescription, but as a diagnosis of the problems of British politics this is a corker. “Soon Britain will just be a gloomy Italy, halfway between museum and nursing home, with nothing to offer the young but emigration, helplessly buffeted by the storms ahead.”

You almost certainly saw the hugely viral story about the fake Indian cricket league invented to fool Russian gamblers, but I’m sharing it here for posterity.

Good bit at the top of the latest Garbage Day about Instagram being retrofitted as an ugly, increasingly useless, general purpose internet portal as users flee the main Facebook app.

“How Pixar Went From Experimental Studio to Commercial Juggernaut”.