Welcome to this week’s free edition of The Terminal. If you’d like to become a paying subscriber and get access to more content, hit the button below.

I co-host the podcast Down Round, which you can subscribe to here. (Now on Twitter!) If you’re listening and enjoying, give us a review on your platform of choice.

Checked out

In a newsletter last month I wrote about the weird system of prestige that had built up around account verification on social media platforms like Twitter and Instagram. What originally began as a practical way to identify real accounts from impersonators developed into a class system that puts celebrities, influencers, journalists and brands on a different level to the great unwashed, and made the blue check into a status symbol. (As in any good aristocracy, the process for reliably acquiring a blue check is opaque and mostly based on who you know.)

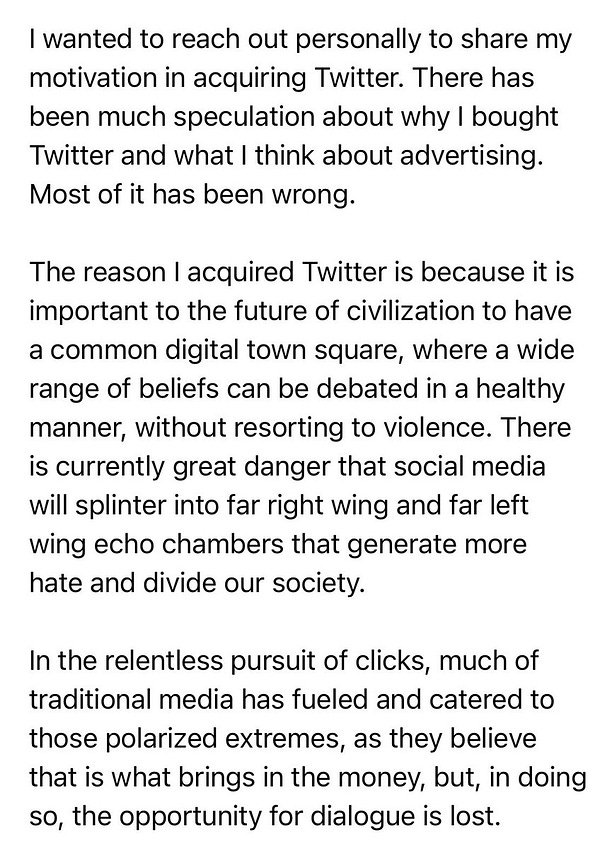

So it’s extremely interesting that the first thing Elon Musk is signalling in his revanchist takeover of Twitter — aside from some flavour of stack ranked layoffs — is paid verification.

Now that he owns Twitter, Elon Musk has given employees their first ultimatum: Meet his deadline to introduce paid verification on Twitter or pack up and leave.

The directive is to change Twitter Blue, the company’s optional, $4.99 a month subscription that unlocks additional features, into a more expensive subscription that also verifies users, according to people familiar with the matter and internal correspondence seen by The Verge. Twitter is currently planning to charge $19.99 for the new Twitter Blue subscription. Under the current plan, verified users would have 90 days to subscribe or lose their blue checkmark.

There are two ways to read this. The first is that this is just an obvious way to eke out money from Twitter’s core base of power users, many of whom are either verified or would love to be. The way it’s structured is deliberately extortionate — cough up or you’ll lose your precious status flex — while also opening the door for the army of grindset guys who would love a juicy, validating blue check next to their threads about sales tactics. If you want the extended reach and benefits of the tick, you should pay for it. It makes sense, in the same way that LinkedIn slugs its power users for its (quite pricey) Premium product, though it doesn’t exactly help make a vibrant platform anyone but recruiters and cold-blooded sociopaths enjoys spending time on.

But the second interpretation is that this makes an interesting bit of culture war. There are plenty of people in the extended Musk war room who would no doubt love to smash up the class system the blue check represents — one that disproportionately favours journalists mainstream media. Replacing the opaque processes which replicate that order with one based on simple willingness to pay makes for a great way to break that up while also making some money.

Also amusing while we’re on Twitter: the return to the glorious era of free speech doesn’t mean there can’t be a little grovelling to the gods of advertising brand safety. Not even the richest man on earth can escape that.

Transistor girls

Allow me to take you down a weird rabbit hole I’ve been pursuing the past few days in lieu of real research on matters of actual importance. I’m currently reading Chip War by Chris Masters, which was released this month. So far, it’s a very readable popular history of the development of semiconductors and the microchip, and the increasingly important geopolitical systems and tensions generated by chip manufacturing and supply chains.

I was struck by one colourful passing anecdote in one chapter: a reference to a trashy Australian pulp novel from 1964 named The Transistor Girls, by Paul Daniels, described as being about about “Chinese gangsters, international intrigue, and women assembly line workers”. As you might be able to ascertain from the cover, these Japanese assembly line workers were also — shock horror — sex workers by night. You can guess how the book plays out from there.

Masters uses this lurid bit of Orientalist erotica to illustrate two things: firstly that early microchips were designed by men but largely assembled by women, and secondly a developing fascination with the semiconductor and transistor industry, which was then exciting and futuristic. American companies had begun pushing semiconductor production to Asia to dodge higher wages and labour unions domestically, establishing early association between a computerised future and Asian culture. (Another great example of the burgeoning cultural fixation with semiconductors, unmentioned in this book, was that the first Iron Man comics in the early ‘60s were heavily focused on the fact his suit was powered by “thousands” of transistors, which did everything from protect his wounded heart to enabling him to shoot antigravity rays from his hands.)

I decided to dig into this, because the prospect of an intersection of forgotten Australian pulp lit and Cold War tech development is, regrettably, extremely my shit. The National Library does indeed carry a copy of the book, which it notes was published by long-defunct Sydney erotic paperback house Stag Publishing. But some cursory research reveals Paul Daniels was a pseudonym of Paul W. Fairman, an American pulp author who churned out innumerable paperbacks in genres from sci-fi to hardboiled detective fiction and gothic romance under a legion of names until his death in 1977.

So where’s the Australian connection here? Turns out Chris Masters got it wrong in his book — The Transistor Girls is not an Australian novel. But, in a standard bit of midcentury pulp fiction marketing, Stag Publishing took the book and churned out a localised clone titled Ne-San — attributed to the truly incredible fake name ‘Jerome Denver’ — which copied the blurb, cover, plot and chunks of text from the original novel, shoehorning in some Australian characters in lieu of the American ones. (I guess if you were a discerning Australian consumer of stupendously racist erotica in the 1960s, you wanted characters you could really relate to.)

A sad end for my pursuit of the sordid Australian connection to early microchip history. But I guess we learned something anyway? Well, not really.

That’s hot

A compelling brief Twitter thread here, which I think has something to it. HotorNot really did pioneer some of the simple incentive structures which went on to drive later social media and dating apps, and it did go into the cocktail of influences behind Facebook. Mark Zuckerberg went on to insist to Congress that Facemash, his HotorNot clone, was a prank and not actually relevant to the creation of Facebook. A 2003 Harvard Crimson article about FaceMash does feature a great quote from Zuck on the website: “I don’t see how it can go back online. Issues about violating people’s privacy don’t seem to be surmountable.”

(Sidenote: I didn’t know that HotOrNot.com is now owned by Badoo, which in turn is a subsidiary of Bumble, though it now has been rebranded as a general chat and dating app.)

Turning red

An interesting tidbit from The Information on the shifting political landscape of Silicon Valley:

Employees of four big tech companies are directing a greater share of their midterm political contributions to conservative candidates than in the two previous election cycles. The Information’s analysis of political giving by employees of Google, Apple, Amazon and Meta shows that 15% of donations have gone to Republican candidates or political action committees this election cycle. That figure is up from 5% in 2020 and 8% in 2018.

On the whole, Silicon Valley’s donor class remains overwhelmingly liberal, with more than $7 million going to Democratic candidates and causes, compared to about $1.3 million for Republican ones.

As it says, the tech industry still leans liberal, as represented by how the donor class behaves. For subscribers I’ve written a few stories here and there about these political shifts, as some aspects of a new builder culture — for want of a better descriptor — push further to the right.

One last thing

Turns out this is real.

Elsewhere

A good essay on the gamelike nature of politics and culture experienced via social media. “Digital discourse creates a game-like structure in our perception of reality. For everything that happens, every fact we gather, every interpretation of it we provide, we have an ongoing ledger of the “points” we could garner by posting about it online.”

The relationship between content production and consumption has long since inverted, with human attention as the primary bottleneck; as the content continues to accumulate, its purpose will evolve. Instead of an output—something to inform or entertain humans—content will increasingly be an input for our massive global culture machine, with AI distilling the existing archive into yet more content in an accelerating cycle.

On ‘Cultural Moneyballism’, the thesis that access to extensive and granular data has led to a beige homogenisation of culture, affecting everything from sports to movies and music. “In a world that will only become more influenced by mathematical intelligence, can we ruin culture through our attempts to perfect it?” (An adjacent critique, of ‘refinement culture’, has been argued by Paul Skallas.)

A feature in Bloomberg on the general rejection of NFTs by gamers, who were supposed to be the vanguard for wider adoption of blockchain-based digital assets generally. It makes the case that, while gamers might be inclined to buy Fortnite skins or other status-flexing cosmetic items, the prospect of financialising their hobby and turning it into a giant stock exchange was significantly less appealing. (The fact the vast majority of NFT-adjacent games are shrewdly manufactured economies first with fun a distant second priority doesn’t help.)

On pickleball, the “combination of badminton, Ping-Pong and tennis” which tennis purists argue is an astroturfed sport for fake fans and non-athletes being seized on as an investment vehicle for rich weirdos. Contains a link to a tongue-in-cheek manifesto by left-wing tennis newsletter Club Leftist Tennis, which accuses pickleball of representing “further entrenchment of the capitalist logic of productivity”. Wonderful.

Francis Fukuyama is back for another bite of the apple: “More Proof That This Really Is the End of History”.

Good summary of the current state of play with microchip sanctions on China.

“Andreessen Horowitz Went All In On Crypto at the Worst Possible Time”.

Regarding apparent shifting political leanings of the tech industry - is there something to be said for the possibility that those earning high enough incomes and in senior enough positions to incentivise political donations are just getting older, and so any metric which measures political views by aggregate donation value by party should be expected to show the same shift by age (older=more conservative) as is seen in the general population?