Public squares and androids dreaming

A late newsletter!

Welcome to this week’s free edition of The Terminal. If you’d like to become a subscriber, hit the button below.

Apologies for the lack of posts this week – I’ve been very, very unfairly blitzed by Covid. If anything in today’s newsletter doesn’t make any sense, I blame my fever and not my brain / writing ability.

The public square

Elon Musk attempting to buy Twitter is an event lab-grown to generate annoying posts, so here’s another one for the bonfire.

Let’s put aside for a moment the diverse and exciting range of theories as to why Musk might want to acquire Twitter, and take him at his word that it is ultimately about safeguarding his vision of a free speech platform. In a letter to the board this week, he said Twitter is “the platform for free speech around the world” but that it can’t achieve that “societal imperative” at present and “needs to be transformed as a private company”.

“My strong, intuitive sense is that having a public platform that is maximally trusted and broadly inclusive is extremely important to the future of civilisation,” he elaborated further at TED2022. He floated the idea of making Twitter’s ranking algorithm transparent, and minimising the use of permanent bans as a disciplinary tool.

Twitter is a weird platform, and it is weirder still that it has become the primary candidate for global public square. But it has. It’s become a central engine of world culture and politics despite being actively used by a negligible slice of the population and run by a company that is perpetually a few feet behind the puck and unsure where to take it.

Despite the fact they are used by many more people — and no doubt have a deeper influence on the public’s political psyche — Facebook and Instagram are rarely discussed in quite the same way as Twitter is. Yes, there are frequent panics about misinformation on, but no one is under the illusion they can be fixed by some outside party in order to achieve some higher civilisational purpose and restore some mythic vision of balance to the broader polity. Calling Facebook a ‘global public square’ might have flown in an undergraduate digital cultures essay in 2009, but certainly not anymore.

Twitter, on the other hand, is perceived as a site of real power. Its moderation policies, long a bugbear for the right, are talked about as if they are a genuine handbrake on broader political function. It’s all the more frustrating for conservatives, given that the legion of ‘free speech’ Twitter alternatives never attract many regular users beyond the wingnuts.

I think the reason for this ultimately comes down to something Max Read put well in a recent newsletter:

If my back-of-the-envelope math is right, about five percent of Americans produce 97 percent of (American) tweets, and I don’t think it’d be going out on a limb if I said that that five percent is probably not broadly representative of Americans. Indeed, what makes Twitter influential, important, and powerful isn’t that it’s a “public” space but that it’s an incredibly elite space: nowhere else are you going to find quite so heavy a concentration of people working in tech, media, entertainment, and politics.

At the end of the day, Twitter operates a two-tiered society. At the bottom there are the proles churning out memes, awards show live-tweets, TikTok reposts, political hashtags and gags like “water from the good tap hits different” that are retweeted five million times, and at the top is an everlasting psychodrama and networking session between the most powerful people in (mostly) Western society. The freewheeling interaction of these two spheres is where all the platform’s energy derives from, and it makes for a system that is virtually impossible to replicate elsewhere. The network effect is totally ossified now.

It’s hard not to read the arguments about Musk taking over through the lens of that upper crust psychodrama. This is not about implementing policies that respect and enable the free speech and social function of a guy who runs an account named @rob4347823 which exclusively posts links to articles about Anthony Fauci and replies “Nice!” to pornstars. It’s about striking a different balance of power among the terminally online media professionals, political figures and posting addicts who make up the sites relatively small core membership. T

The bet among all the people agitating for it — and trying to stop it — is that it will have second-order effects throughout actual human society. But I do wonder whether that constant factional negotiation, which Twitter tries (mostly incompetently) to depoliticise, is something Musk actually wants on his plate.

Interlude

Apologies for writing at length about Twitter. Have this instead. Apparently it’s a long-time ongoing bit for this kid.

I paint therefore I am

Readers of this newsletter will know I am very interested in the role generative AI will play in cultural production in the future. I do my part to surrender my creative will to the singularity by including an AI-generated lead image on each newsletter.

The latest from that world is DALL-E, a version of GPT-3 from OpenAI which is trained to generate images from text strings. Unlike other recent engines, DALL-E can interpret reasonably sophisticated inputs and “explore the compositional structure of language”. From the site:

We’ve found that it has a diverse set of capabilities, including creating anthropomorphised versions of animals and objects, combining unrelated concepts in plausible ways, rendering text, and applying transformations to existing images.

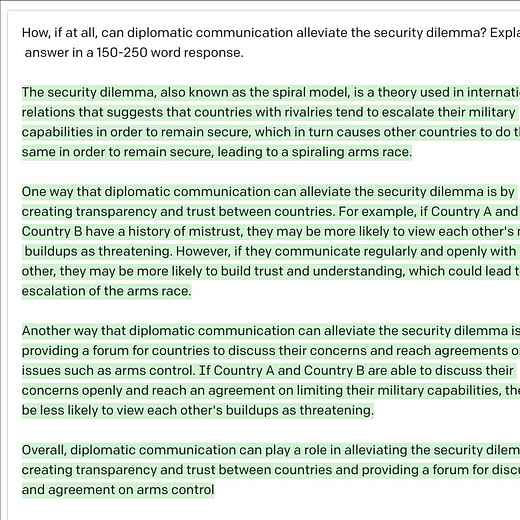

I’ve applied for access, but haven’t received it yet. (Again, humble newsletter writers are spurned and disrespected.) Instead, here’s a few examples I’ve plucked from social media, to give you a sense of how well it captures both complicated, information-dense inputs as well as simple prompts:

As you can see, it’s extremely impressive, even if a cursory look at any of these images reveals it falls apart at the finer details. Look at that cat’s fork. Disgusting.

It does seem to escape the problem that afflicts most image generation systems — like Wombo Art — which is that, once you’ve looked at dozens of its output images, it all starts to look a little bit samey. Usually, you pretty quickly start to get a feel for how the sausage is made, and you notice consistent themes, visual motifs and routine imperfections. (The unsettling, psychedelic forms of early neural network art is an extreme example of this.) DALL-E’s outputs, on the face of it, seem more diverse — helped by the fact it accepts more detailed instructions on visual style.

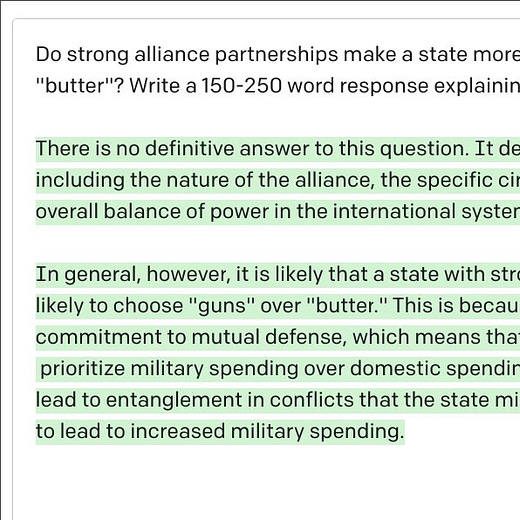

This also came across my feed:

As Kenkel notes down the thread, none of the AI-generated answers would come out at the top of the class. But they’re perfectly serviceable and the prose is “top quartile”. “In terms of substantive quality, these answers are at or just below the median of what I typically see,” he added.

This stuff is only going to get more advanced in the very near future, and I’m less interested in how close it can get to approximating human creative and intellectual output, and more with how we deal with it on a social level. What does it mean for creative and informational industries and those employed in them? Do we re-evaluate the form art and critique take? Do we outright ban use of generative language models in education, or find a way to integrate them?

I don’t think we’re at cyberpunk fantasia level just yet, but these questions are more urgent than you might imagine.

War machines

Another AI story for you, while we’re at it:

The firm in question here is Clearview AI, founded by Australian Hoan Ton-That. It’s best known in recent years for selling its facial recognition tech to law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

Reuters reported last month that Ton-That had offered its tech to Ukraine, and that it had “more than 2 billion images from the Russian social media service VKontakte at its disposal”.

Elsewhere

Here’s a great interview by Nilay Patel at The Verge with Chris Dixon, who leads leads crypto and Web3 investing at Andreessen Horowitz. Dixon is one of the most public and influential Web3 evangelists, and here Patel presses him hard on basically every issue you can think of with regards to the blockchain and NFTs. The general thrust of the interview can be summed up as: why do we need crypto, the blockchain and NFTs to do the stuff you say you want to do, and when can we expect it to actually start working? I don’t think Dixon really provides particularly compelling answers to either of those broad questions, but you be the judge.

On Gen Z’s “new favourite app” BeReal. “BeReal encourages users to send one post every day to their friends to show exactly what they're doing in real time…. in a push toward authenticity, the app snaps photos from the phone's front and back cameras simultaneously, showing where you are and what you’re doing at the same time.” The reaction against overly sanitised and planned social media lives inevitably tends towards artificially enforced spontaneity.

This post is about the the political situation of Canadian housing market, but it very neatly describes Australia’s too.

Liked this on conservative postliberalism and one of its leading advocates, Harvard law professor Adrian Vermeule.

The New York Times has a story about Jordan Belfort — a.k.a The Wolf of Wall Street — and his hard pivot into crypto and NFTs. I’ve been served a bunch of his weird NFT hustle mindset stuff on TikTok.

The US government thinks that Lazarus, a syndicate associated with North Korea, is behind the massive Axie Infinity hack.

A short essay on the ‘chilling fog of content’ and how the Russia-Ukraine war is read and perceived online.

Someone did a simple data analysis of r/AmITheAsshole. “Posters were 64% female; post subjects (the person with whom the poster had a dispute) were 62% female. Posters had average age 31, subjects averaged 33… Male posters were significantly more likely to be the assholes. They made up only 23% of the NTA posts but 60% of the YTA posts.”