A haunting in Connecticut

A journey into the dark, twisted heart of America...

Since we’re all sitting at home anyway, I thought I’d kick this newsletter back into gear — starting with a story.

Anyone who has done any kind of entertainment journalism will be intimately familiar with the junket. Probably pound-for-pound one of the more cost-effective ways of marketing a film, it generally involves a movie studio throwing together an itinerary of activities related in some way to the movie and inviting a bunch of journos and content producers along to take part. Generally, it involves set visits, interviews with the cast and directors, some nice meals on the studio’s dime, and usually something fun and visual which makes for good video or, at least, a colourful story. They pay for little more than the accommodation, airfares and entertainment, and boom — they’ve got content live across a series of platforms without having to fork out for display ads and sponsored posts. Not a bad deal!

(This may be obvious to you, but sometimes people are surprised about how this stuff works, so I thought I’d lay it out anyway.)

Early last year I got invited — very last-minute — to a junket for Annabelle Comes Home, the third entry in the Annabelle series and the seventh in the universe of The Conjuring, a rich corpus of work which explores the nuances of an age-old question: would it be scary if ghosts were real? (Answer: yes, intermittently.) The pitch for this particular junket was simple: no cast, director, or set access, but you got to see the real Annabelle. In many ways the most valuable access of all.

In short, I did a 32,000 kilometre round trip from Sydney to Monroe, Connecticut, all in the space of about four days, so I could see a haunted doll.

Some background for those less emotionally invested in American paranormal kitsch than I am. The Conjuring movies fictionalise the ‘case files’ of Ed and Lorraine Warren (played capably by Patrick Wilson and Vera Fermiga), a pair of psychic investigators who researched — and, one could easily argue, promoted — supernatural phenomena in the second half of the 20th century. Founding the New England Society for Psychic Research in 1952, the Warrens were in the orbit of just about every nebulously evidenced haunting, possession or demonic incursion which made headlines during a long period of public fascination with the occult. We’re talking Amityville, the Enfield poltergeist, the Snedeker house — they were on the scene for all of them, tapping Lorraine’s professed psychic gift in effort to banish malevolent spirits back to the netherworld.

Aside from their ghost hunting business and their various travels on the lecture circuit, the Warrens also ran a an ‘occult museum' in a shed out the back of their house in Connecticut, where they kept an assortment of items which looked like either cursed talismans of unimaginable power or shitty plastic junk shop cruft, depending on how hard you squinted. Among these items was Annabelle, the Raggedy Ann doll that inspired a billion dollar movie franchise, which the Warrens maintained was possessed by an evil entity masquerading as a deceased girl of the same name.

Back to the story. The shepherd for this curated trip was Judy Warren, daughter of the Warrens and character in the Conjuring films, and her husband Tony Spera. There was one clear stipulation from Warner Bros: whatever you ended up producing from this trip, it could not fundamentally question or ridicule the beliefs of the hosts. Well, fine. Far more Faustian bargains are made in media every day for access, so if I was being asked only to acknowledge an elaborate Catholic eschatology in which restless spirits wander the earth and inhabit dolls could be real, so be it. I’m an open-minded guy.

Here’s where things get interesting, on a few fronts. Let me set the scene.

Firstly, this trip took place early in June 2019. Lorraine Warren died just over a month earlier, at the age of 93. It was so recently, in fact, that I have to assume the junket was being planned while she was still alive. As you might imagine, this made the experience far stranger than it would have been otherwise.

Secondly. Those who have seen Annabelle Comes Home will know that Judy Warren — as a child — is the main character of the film. However, it isn’t actually based on any of the Warren case files. Or anything, actually. It’s a purely fictional haunted house romp in which Judy and her friends accidentally knock open Annabelle’s case and unleash a series of evil entities including a werewolf made out of smoke. I really want to stress at this point that Judy is a person who, to my knowledge, has never been forced to do battle with any sort of werewolf. I also had the pleasure of being in the cinema while Judy saw the movie for the first time. So I got to see her watch a film, featuring herself but based on nothing in particular, in which she is terrorised by demons. (Her verdict: “Pretty good!”)

Thirdly: it quickly became apparent that I was one of very few actual writers who were invited on this trip. The majority of the guests were paranormal YouTubers. These are people who do true crime style breakdowns of supernatural phenomena, and run around in cemeteries with GoPros attempting to capture evidence that ghosts are real. I don’t consider myself above them in either mission or craft. As I said, I’m just setting the scene.

We were taken, by Judy and Tony, to what they described as the most haunted cemetery in America: the Union Cemetery in Easton, Connecticut. It’s a small expanse of grass nestled between a two-lane highway and a forest. Tony, who said he was a no-nonsense cop who didn’t believe in the paranormal until he met Ed Warren, explained how one could take a photo of a ghost. His method, which I will not divulge here out of respect, did not work for me. Here’s a photo of me in the cemetery instead.

The spectral figure over my shoulder is not a ghost. It is a YouTuber.

We were shepherded to another cemetery, about fifteen minutes drive away, where Ed and Lorraine Warren are interred. A far more austere space — situated across the road from the glowing neon sign of a pizza joint — the final resting place of America’s most famous demonologists certainly struck me as less haunted than Union Cemetery, though I saw the same number of ghosts at both (zero). I stood with a cluster of YouTubers next to Ed and Lorraine’s grave. Judy was understandably very upset, openly weeping as Tony spoke. Her mother had passed away only weeks before.

I think that was the point when I realised, “Oh, this isn’t a movie junket, this is maybe one of the weirdest things I will ever experience in my life.”

The whole time this was going on, as Tony told stories about ghostly encounters and his own experience with the supernatural, I was trying to divine an answer to the eternal question: are these people frauds or not? This is the question which pursed Ed and Lorraine for their entire careers. Did they really believe in this shit? Or was it all part of a great American tradition of hucksterism and flimflammery? This was the allegation raised by a generation of skeptics, as the Warrens and the cases they pursued made headlines — that they were carnival barkers profiting off a folkloric tradition much older than themselves; deft manipulators of the often hazy boundary between myth and the pop cultural id. The fact I was there as a guest of Warner Brothers to market a blockbuster film certainly pointed to it all being spectacle in the P.T. Barnum mode.

But I didn’t walk away with a clear answer. They struck me as true believers, at least on the face of it. It’s possible both angles are true, in quintessentially American form: the Warrens could be people who have bought the grift so completely that it inhabits their very pith and sinew. Surrounded by ghost vloggers with millions of subscribers between them — whose genuine beliefs were about as unclear — I got the sense the kayfabe ran very deep.

To underscore all this: when we arrived at the occult museum, late at night, we were greeted by someone purporting to be a deacon from the local Catholic Church, who made a great show of blessing us with holy water and oil before we entered what he described as a place of great and genuine evil but was was in reality a musty roadside attraction full of Halloween masks and paperback occult literature. I don’t know if he was who he said he was, or to what extent the Vatican endorses that kind of thing, but good on him.

The occult museum is permanently closed now. I had a very brief conversation afterwards with Judy afterwards, who said she was planning to sell the house — and therefore the property on which the museum stood. What should have been a relatively easy property transaction, she said, was complicated by the unique nature of the objects kept on-site.

“You can’t just put these things in a box and move them,” she said. “This is powerful stuff.”

This was quite long! I hope you enjoyed it. Here’s me with Judy and Tony, and the real Annabelle prop from the movie (NOT the real Annabelle).

What I’m reading…

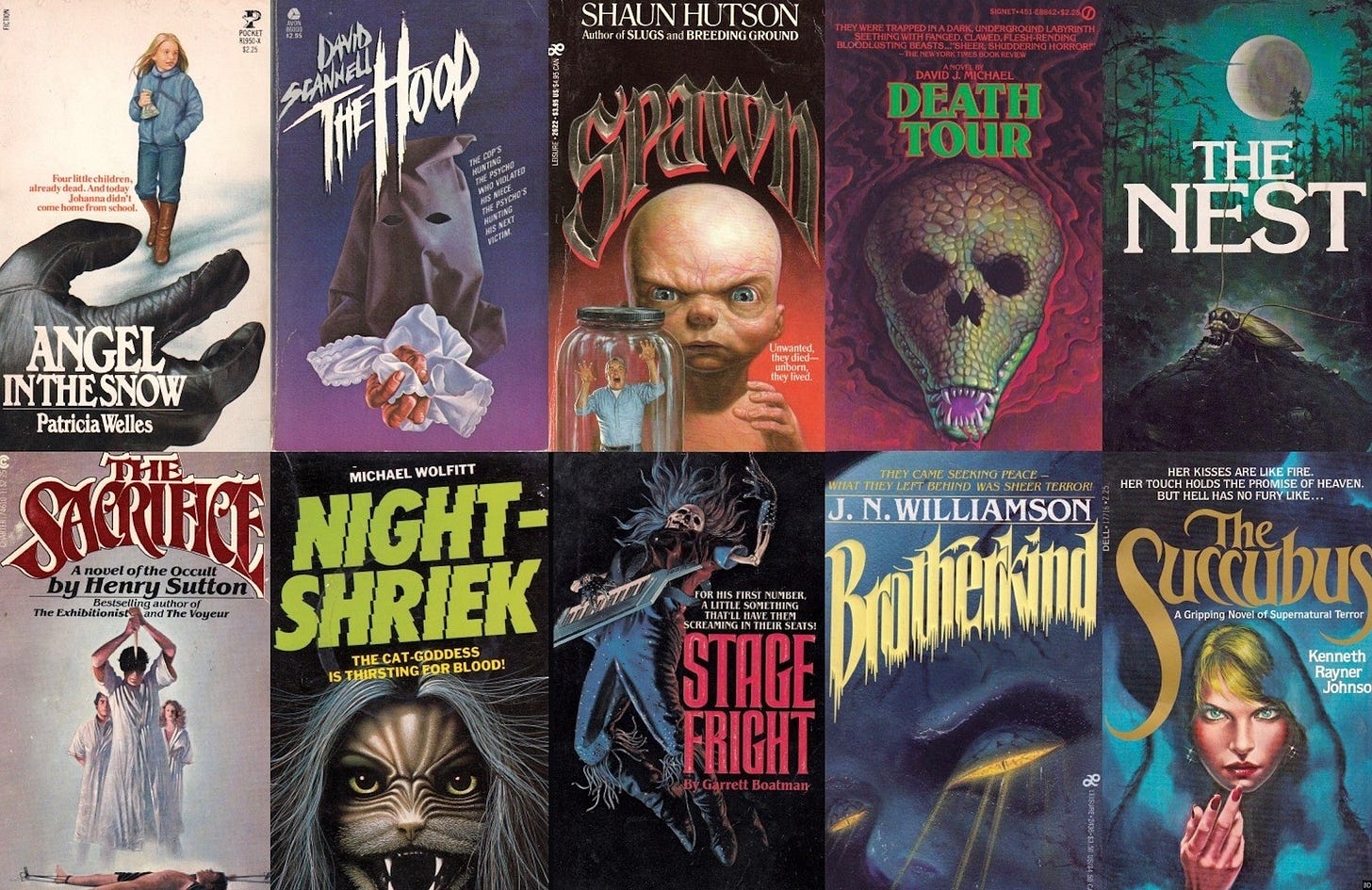

Paperbacks from Hell: The Twisted History of ‘70s and ‘80s Horror Fiction - Grady Hendrix. For reasons entirely unrelated to my mental state in coronavirus quarantine, I’ve been churning through a stack of old horror paperbacks over the past month or so. The Hendrix book is a fun little survey you can tear through in a few hours, and serves as a useful signpost towards more obscure titles, if you feel so inclined. Don’t expect a particularly deep history, though there are some decent insights into the ruthlessly commercial instincts behind the glut of bottom-tier pulp during the period, and the mercenary outfits which exploited the trend. It’s pretty funny, too:

Some writers overpromised, depicting computers as superheroes. Stephen Gresham, author of The Shadow Man (1986), believed that personal computers could generate hard-light holograms capable of running our errands, but then again Gresham also believed that pro wrestling was real, so he might have been a simpleton.

Also, a great compendium of paperback horror covers, which is why I recommend either getting the physical book or at least reading it on something with colour.

The Elementals - Michael McDowell. One of the more fruitful expeditions from the above was actually a reread of something I first encountered as a teenager. McDowell, who went on to write the screenplays for both Beetlejuice and The Nightmare Before Christmas (before dying of an AIDS-related illness while partway through a sequel to the former) was a cut above many of his contemporaries in the space. The Elementals, while basically being a haunted house weird tale, works so well because it’s also great entry into the Southern Gothic canon — with all the sunbaked Alabama heat, old Victorian-era mansions, decaying aristocracies and weird family rituals one expects.

The Dog of the South - Charles Portis. Another revisit I put on my list when Portis died earlier this year. Unbelievably funny novel, one of the funniest things ever written. Every paragraph knocks me flat.

I had sat next to Dupree on the rim of the copy desk. In fact, I had gotten him the job. He was not well liked in the newsroom. He radiated dense waves of hatred and he never joined in the friendly banter around the desk, he who had once been so lively. He hardly spoke at all except to mutter “Crap” or “What crap” as he processed news matter, affecting a contempt for all events on earth and for the written accounts of those events.

I have a weird fascination with extreme coronavirus contrarians right now — not necessarily everyone who think the international response has been overblown or misdirected, but specifically the ones who hinge that argument on the virus itself not being a big deal, even as it racks up a higher and higher body count. I thought this Vanity Fair piece about Alex Berenson, the spy novelist and former NYT journo whose entire Twitter feed is a swamp of this stuff, was interesting.

What I’m watching…

Dark Waters [dir. Todd Haynes]. This movie really fits into a kind of subgenre of the bog standard legal thriller I’d call ‘legal horror’ (this is a very horror-heavy newsletter and I apologise). Last year’s Iraq War torture flick The Report also fits under this banner. Exploring DuPont’s coverup of the poisonous waste produced by the Teflon manufacturing process, much of the first third of the film plays out with the aesthetic of an early aughts torture porn: drunken teenagers swimming in a toxic lake, grainy VHS footage of mutations and deformities, mad livestock being executed with rifles. The Report did similarly with heavy metal recreations of CIA torture atrocities in Iraq. Both movies eventually settle into standard, information-dense legal procedurals, but the setups — intended as much to scare and sicken as much as provide factual context — feel like a new mode to me.

Also, this serves as a great followup to Haynes’ insanely ahead of its time 1994 film Safe, in which Julianne Moore plays an LA housewife who develops hypersensitivity to industrial chemicals and relocates to a self-help hippie cult/commune in the desert.