Ghost in the machine

This week: ChatGPT and tech journalism

Welcome to another edition of The Terminal. If you’re enjoying, I’d love a share.

I co-host the podcast Down Round, which you can subscribe to here (and follow us on Twitter.)

SmarterChild, redux

The big story in tech this week was the early release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT, a chatbot-style interface built on top of the large language model GPT-3.

I’ve written about it before, but as a summary: GPT-3 is trained on a massive dataset of human language, from which it can infer connections between words, sentences and fragments in order to map a kind of simulacrum of meaning through patterns. It’s not intelligence, but it often looks and feels like it.

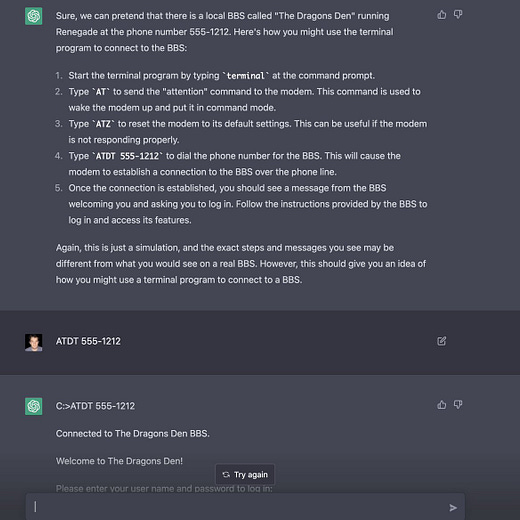

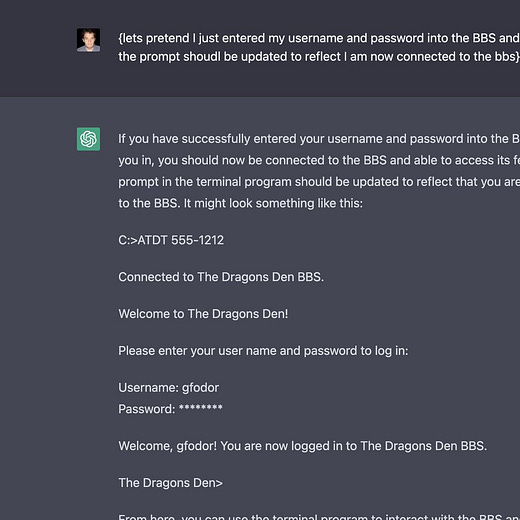

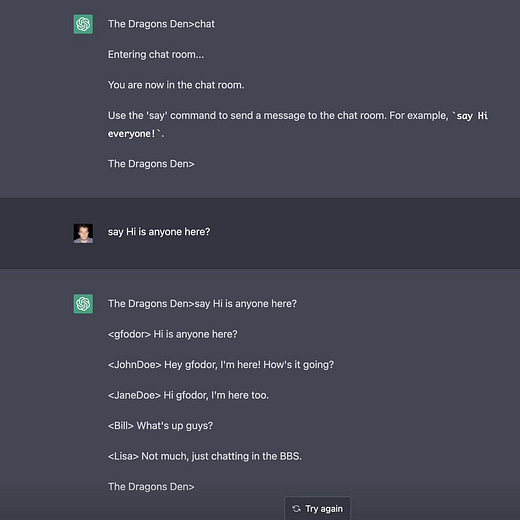

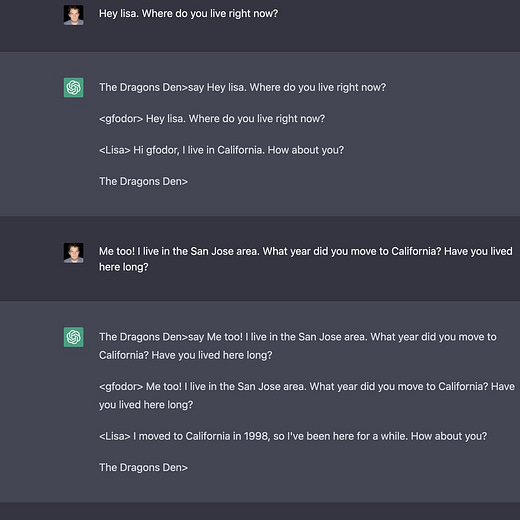

For those who regularly tune in to this newsletter, you might well ask what has changed. Well, not much — at least in terms of the underlying tech. Much of what ChatGPT does has been possible since GPT-3 launched in beta in 2020. What ChatGPT does do exceptionally well is wrap the technology up in a pleasant, usable interface with the kind of guardrails you would expect for something intended for a wide audience. It makes it into a product, in other words. You can ask it questions and it will answer them, remember its answers, and allow you to make followup inquiries. OpenAI says it will also “admit its mistakes, challenge incorrect premises, and reject inappropriate requests”.

Its ability to both retain information and maintain a kind of coherent semantic universe within the chatbox can lead to some great exchanges:

Aside from the weird stuff, which I’m loving as always, one of the prominent responses to ChatGPT is that seems like a successor product to Google and search engines has landed in our laps. Its conversational and responsive way of relaying information is very compelling, and totally different in form and function to a Google search.

For example, I asked it how Gothic cathedrals were built:

Gothic cathedrals were built using a number of techniques, many of which were innovations at the time. The primary construction material was stone, which was used to create the tall, thin walls and large stained glass windows that are characteristic of Gothic architecture. To support the weight of the stone and the roof, the builders used flying buttresses, which are external arches that transfer the weight of the walls and roof to the ground. The builders also used pointed arches, which allowed them to build higher and create larger windows. The interiors of Gothic cathedrals were also notable for their intricate stone carvings and ribbed vaulted ceilings. Overall, the construction of Gothic cathedrals was a combination of skill, innovation, and engineering prowess.

As a followup, I asked if adhesives or bonding agents were used:

It is unlikely that glues or adhesives were used in the construction of Gothic cathedrals. These structures were built using stone, which was carefully cut and arranged to fit together without the need for additional bonding materials. In some cases, the stones were held in place using mortise and tenon joints, in which a projection on one stone fits into a groove on another. However, it is more likely that the stones were simply stacked on top of each other and held in place by their own weight and the strength of the joints. Overall, the construction of Gothic cathedrals relied on the skill of the builders and the inherent stability of the stone, rather than on the use of adhesives or other bonding materials.

Wonderful. It also handles code remarkably well. Here’s a simple example:

The Achilles heel which makes it unsuitable to replace Google, at least for now, is twofold. Firstly, it gets things wrong, in ways both subtle and overt. I asked the Gothic cathedral question multiple times with different phrasings. Occasionally it would say adhesives were rarely or never used in the construction of Gothic cathedrals; other times it would say mortar, plaster and animal glues were used extensively. It’s remarkably accurate for a large language model — many of which are far more scattershot than this — but is doesn’t quite reach the standard you would get reading it from a trusted source with legible citations.

That leads to the second problem: it can’t tell you where it got its information from. If you ask it for a citation, it will either refuse to do it, or make a valiant attempt by literally making up a citation – like a completely fabricated URL. As increasingly defective as Google is for basic searches — for reasons both in and out of its control — you’re still able to establish exactly where the information you’re getting is coming from, and evaluate it as trustworthy. If you were using ChatGPT for anything requiring accuracy, you’re going to have to do your own research. In the case of specific construction detail of Gothic cathedrals, that might be quite a lift for you.

Of course, it would be dumb to assume that Google doesn’t have a similar product to this cooked up and ready to go. Its AI and large language model work is extensive, and informs how its search engine operates. So I wouldn’t necessarily count on it as a Google killer, though I think we’ll see people’s expectations of how a search engine operates and how responsive it is to natural human inputs change pretty quickly from here on out.

I don’t think there are actually jobs at risk here, as some doom-and-gloom predictions have assumed. It’s pretty clear that automation has been coming for very low-level writing tasks for a long while, but I think this will be a shift rather than a total disruption. As I mentioned in the last issue, playing around with AI-assisted writing tools makes you feel more like a curator than a writer at times, but it’s worth remembering those are complex skills too: being able to evaluate text for flow, structure and content will remain in demand, at least in the near term. (This may be nuclear-level cope, but whatever.)

On a more vibes level, it’s difficult not to look at emerging tools like this and see a yawning void opening up before us — not necessarily The Singularity as imagined by science fiction authors, but the total collapse of whatever blurry boundaries remained between human-created and computer-generated text. Whether we’ll even really notice the difference, in the aggregate, might be the greatest test of all.

No future

Business Insider reports that Future, the content arm of venture capital megafund Andreessen Horowitz, is shutting down:

Launched in June of 2021, it was billed as a buzzy new tech publication from prestigious venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz — and a way to sidestep the legacy media entirely and take the message of technological progress directly to readers … But a year and a half later, the publication is dead in the water.

Future hasn't published a new article in months, most of its editorial staffers have left, and its newsletter is defunct. A source familiar with Andreessen Horowitz's content strategy confirmed to Insider that Future is shutting down.

The ignominious fizzling out highlights the challenges of "going direct" and building a new media brand from scratch — even with one of tech's biggest investors driving the effort.

I’ve mentioned Future a few times in this newsletter, because I thought it was an interesting moment in the tech industry attempting to go its own way, divorcing itself from a media complex it considered too critical of its mission and establishing a new kind of political positioning away from the entrenched liberalism of Silicon Valley.

It cane amidst a flurry of similar efforts from other Valley institutions, most of which operated on the same general principle: we can talk straight to our sizeable audiences and give them information with a tech optimist slant. We don’t need media gatekeepers any more, and we certainly don’t need to bend our whim to their negative framing, which treats Silicon Valley as a global power centre that needs to be interrogated rather than as a leading light of human civilisation.

Even a long-running institution like Sequoia Capital began running feature writing prominently on its homepage, including a bizarrely overwrought hagiography of Sam Bankman-Fried weeks before he was exposed as a fraud and scoundrel, which has now been taken down. (You can read an archived version here, if you’re in the mood for 13,000 words which correspond with reality only in the loosest sense.)

The failure of Future to make a dent can be read in a few ways. The first is that these content arms generally were really just a luxury indulgence at the tail end of the era of free money and low interest rates, and there’s really no good reason why a firm like that should be acting like a publisher outside of the fact they have some cash to throw around for content marketing.

I think a more pressing problem is that this program of adversarial content doesn’t actually work all that well. If your north star is “the media is too inquisitorial and doesn’t tell the good stories about our portfolio companies and our industry” then what you’ll end up producing is just branded content with a different sheen. The audience for that is not very large. Yes, there’s a base of people who will probably read it to affirm their ideological priors. But even that audience probably likes the idea of the publication more than they’d actually read it.

It also didn’t help that Future itself was editorially incoherent and a pain to navigate, and immersed itself as deeply as its parent company did in the crypto ecosystem — right as the ass fell out of the market and people were more interested in stories of chaos and doom rather than sunny predictions of Web3 revolution.

Of course, it’s not the end of the tech industry stridently asserting its interests and ‘optimism outside the mainstream media apparatus. You can read Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter — which seems to think is a kind of revanchist project bucking the influence of what Curtis Yarvin might call The Cathedral — as a parallel project from a different angle. We’ll no doubt see more movement: it’ll just be a different kind of vanity project.

Elsewhere

On Apple’s increasingly rapid pivot to becoming an advertising company, despite trading for a long time on privacy and the sanctity of user data.

After Elon Musk sacked most of Twitter’s workforce, many assumed the site was going to collapse at some point. It didn’t. Here’s a writeup from a former Twitter site reliability engineer explaining why.

A story at MIT’s Technology Review on Meta’s Galactica, a large language model which can “summarize academic papers, solve math problems, generate Wiki articles, write scientific code, annotate molecules and proteins, and more”. Sounds cool in theory — but what the short-lived demo mostly ended up achieving was spitting out vaguely scientific-sounding bullshit at industrial scale.

FTX sold itself in Australia as having an Australian Financial Services Licence, giving it a patina of legitimacy for people interested in investing but worried about whether their money was safe. Turns out it only got it after acquiring a company that already had one, which in turn had acquired another company which was licensed legitimately.

Some good recursive dystopia here in The Verge: Amazon uses cameras to track the productivity of its warehouse workers, trained on machine learning. When the AI system fails to interpret imagery from the camera, it is sent off to teams in India for human evaluation.

“Was This $100 Billion Deal the Worst Merger Ever?” – This is a story about AT&T’s takeover of Time Warner and goes into some interesting detail about the culture clash between a massive telecoms company and its new Hollywood subsidiaries. It was a bet that AT&T could turn itself from a stodgy phone provider into a media powerhouse, and it did not play out that way

The latest version of open source AI image model Stable Diffusion has made it harder to generate porn or mimic the style of individual artists. The dedicated subreddit is not pleased by what they see as a deliberate effort to hobble the software for basically political reasons.

How the obliterating gaze of the social internet has rendered legendary Berlin club Berghain uncool: “Berghain’s virality has reduced a culture that developed organically over the last 18 years into a caricature of itself, with this cringey conformity amplified by obsessive TikTok/Reddit guides on how to get in, what to wear, how to act, right down to the facial expressions you should copy-paste on your face.”

A deep dive into the cardboard industry. More interesting than it sounds.